CCHR dispels the myths attributed to Szasz, an iconic psychiatrist who defied “psychiatric slavery” and “totalitarian control,” and whose works against coercive psychiatry are now recognized the world over, even by the UN.

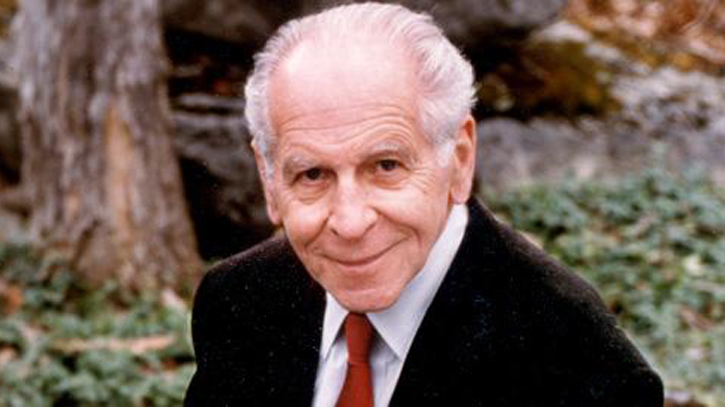

September 8 marks the eight-year anniversary of the death of Thomas Szasz, an iconic professor of psychiatry, co-founder of the mental health industry watchdog, Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR), and one of the most prolific authors against coercive psychiatry. With more than 35 books published since 1961, he challenged conventional psychiatry, including in Psychiatric Slavery, where Szasz took aim at psychiatric interventions imposed on persons by force, including involuntary commitment and treatment.[1] CCHR recognizes the changes in international views on enforced psychiatric treatment as a legacy of what Szasz pioneered nearly 40 years ago.

Publisher’s Weekly described Psychiatric Slavery as Szasz putting the “American psychiatry and legal establishment on trial, with disturbing results. He investigates abuses in diagnostic methods, electroshock ‘therapy’ and judicial apparatus.”[2] Szasz, who was a professor of psychiatry at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University and a distinguished lifetime fellow of the American Psychiatric Association, said, “Involuntary mental hospitalization is like slavery. Refining the standards for commitment is like prettifying the slave plantations. The problem is not how to improve commitment, but how to abolish it.”[3]

An estimated 400,000 Americans are involuntarily committed to psychiatric facilities every year and potentially forcibly drugged.[4] African Americans are disproportionately subjected to coercive and restrictive measures, including 72-hour involuntary commitment, seclusion, restraints and forcibly drugged.[5] Szasz’s works should serve as a warning to African Americans today facing psychiatric recommendations for more “mental health services” and government funds allocated to psychiatrically treat the impact of racism.

The collaboration between government and psychiatry results in what Szasz called the “Therapeutic State,” a system in which disapproved thoughts, emotions, and actions are repressed (“cured”) through pseudomedical interventions.[6] For example, during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, psychiatrists invented the term “protest psychosis” to diagnose Blacks marching against racism as mentally ill.[7] Advertisements for powerful antipsychotic drugs in psychiatric journals used pictures of angry Black men to influence the prescriptions of these damaging drugs to African Americans.[8]

Szasz would have argued that such “classification” is an example of how psychiatrists what they claim to be “(mis)behavior as illness,” which “provides an ideological justification for state-sponsored social control”—a form of totalitarianism.[9]

Szasz was often been misquoted that he didn’t believe in “mental illness,” but this was psychiatrists and front groups misconstruing his ideas and obfuscating the fact that he simply said behavioral disorders are not physical diseases. Szasz asserted that psychiatry, unlike medicine, could not provide any physical test to demonstrate mental problems as “diseases” to be “treated.”[10]

He was very clear on this point, stating: “In asserting that there is no such thing as mental illness, I do not deny that people have problems coping with life and each other.” Szasz never denied that organic conditions—such as Alzheimer’s disease or untreated syphilis—can have an impact on thought and behavior.[11]

Today, that view is accepted medical fact. As the American Psychological Society reported: “Diagnosing mental illness isn’t like diagnosing other chronic diseases. Heart disease is identified with the help of blood tests and electrocardiograms. Diabetes is diagnosed by measuring blood glucose levels. But classifying mental illness is a more subjective endeavor. No blood test exists for depression; no X-ray can identify a child at risk of developing bipolar disorder.”[12] This is “Szasz 101.”

An interview with Szasz published in Reason in 2000 pointed out that “people do seem to be more skeptical than they used to be of psychiatry’s attempts to medicalize behavior. Psychiatrists themselves often acknowledge that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is increasingly arbitrary and unscientific.”[13] Indeed, in 2013, DSM5 was met with mental health professionals calling for an international boycott of the manual.[14]

The chemical imbalance in the brain causing depression theory has been completely discredited—invented by psychopharmaceutical makers to sell SSRI antidepressants. In February 2020, Philip Hickey, Ph.D., a retired psychologist, went a great deal further stating: “The spurious chemical imbalance theory of depression is arguably the most destructive thing that psychiatry has ever done.”[15]

Szasz maintained throughout his career that he was not “antipsychiatry” but was rather anti-coercive psychiatry. He opposed involuntary commitment and enforced treatment.[16] His legacy is now embedded in United Nations documents.

- 2013: The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture recommended: “Impose an absolute ban on all forced and non-consensual medical interventions against persons with disabilities, including the non-consensual administration of psychosurgery, electroshock and mind-altering drugs such as neuroleptics, the use of restraint and solitary confinement, for both long- and short-term application. The obligation to end forced psychiatric interventions based solely on grounds of disability is of immediate application and scarce financial resources cannot justify postponement of its implementation.”[17]

- 2017: UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Dr. Dainius Pūras, called for a revolution in mental health care to “end decades of neglect, abuse and violence.” “There is now unequivocal evidence of the failures of a system that relies too heavily on the biomedical model of mental health services, including the front-line and excessive use of psychotropic medicines, and yet these models persist,” Dr. Pūras, said.[18]

- 2018: UN Human Rights Council (HRC) supported a ban on all forced medical interventions against persons with disabilities, including the administration of electroshock, psychosurgery, and mind-altering drugs. HRC strongly stated that countries “should reframe and recognize these practices as constituting torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment….”[19]

As a libertarian, he equated coercion with slavery, quoting Abraham Lincoln, who said: “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think, and feel.” To which Szasz added: “I knew very little about Lincoln when I grew up in post-World War I Hungary. But I did recognize, as a gut feeling, that if the domination of the mental patient by the psychiatrist is not wrong, then nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think and feel.”[20]

Dr. Szasz: “I am probably the only psychiatrist in the world whose hands are clean. I have never committed anyone. I have never given electric shock. I have never, ever, given drugs to a mental patient.” It is a legacy that the mental health system today sorely needs.[21]

Szasz became a co-founder of CCHR in its forming year, 1969, through an involuntary commitment case where a fellow Hungarian had been labeled as “schizophrenic” when as Szasz found he was simply speaking Hungarian and no-one could understand his protest of being locked up against his will. Szasz said of CCHR: “We should honor CCHR because it is really the organization that for the first time in human history has organized a politically, socially, internationally significant voice to combat psychiatry. This has never happened in human history before.”

References:

[1] https://selfdefinition.org/psychology/Thomas-Szasz-Psychiatric-Slavery.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] https://www.cchrint.org/about-us/co-founder-dr-thomas-szasz/

[4] Gerbasi, JB and Simon, RI, “Patients Rights and Psychiatrists’ Duties: Discharging Patients Against Medical Advice,” Emergency Medicine News, July 2016, Vol. 38, Iss. 7, pp. 14-17, journals.lww.com/em-news/Fulltext/2016/07000/InFocus__The_Risks_of_Discharging_Psych_Patients.8.aspx

[5] https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/USA/INT_CERD_NGO_USA_17741_E.pdf

[6] “Curing the Therapeutic State: Thomas Szasz interviewed by Jacob Sullum,” Reason, July 2000, https://reason.com/2000/07/01/curing-the-therapeutic-state-t/

[7] Jonathan M. Metzl, The Protest Psychosis, How Schizophrenia became a Black Disease, (Beacon Press, Boston, 2009), p. xiv.

[8] “The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease,” Amer. Journ. Of Psychiatry (online), Apr. 2010.

[9] Op. cit., Reason

[10] https://aeon.co/essays/the-psychiatrist-who-didn-t-believe-in-mental-illness

[11] Op. cit., Reason

[12] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/roots

[13] Op. cit., Reason

[14] https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/saving-normal/201302/dsm-5-boycotts-and-petitions

[15] https://www.madinamerica.com/2020/02/chemical-imbalance-theory-going/

[16] https://aeon.co/essays/the-psychiatrist-who-didn-t-believe-in-mental-illness

[17] A/HRC/22/53, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez,” United Nations, General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Twenty-second Session, 1 Feb. 2013, p. 23, Point 4 (89) (b), https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A.HRC.22.53_English.pdf

[18] “World needs ‘revolution’ in mental health care – UN rights expert,” http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21689&LangID=E#sthash.MMIxDbIx.dpuf; http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21689&LangID=E

[19] “Mental Health and Human Rights,” United Nations Human Rights Council, 39th session; 10–28 Sept. 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/MentalHealth/A_HRC_39_36_EN.pdf.

[20] https://www.thenewamerican.com/usnews/health-care/item/12839-the-passing-of-dr-thomas-szasz

[21] http://articles.latimes.com/print/2012/sep/17/local/la-me-thomas-szasz-20120917-1

SHARE YOUR STORY/COMMENT