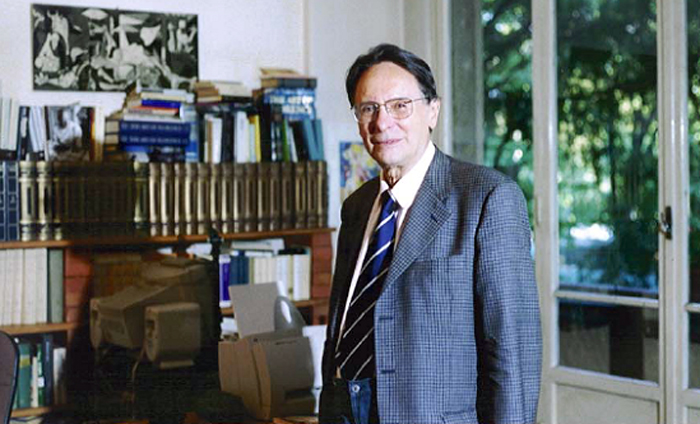

CCHR Commissioner Giorgio Antunucci, 1933-2017

By CCHR International

Mental Health Industry Watchdog

December 4, 2017

Dr. Giorgio Antonucci, the renowned Italian physician and psychotherapist who helped pioneer successful non-drug, non-invasive care for those with mental health problems, died at age 84 on November 18. A Commissioner of Citizens Commission of Human Rights International (CCHR), he fought to prevent and abolish forced psychiatric treatment, to liberate those incarcerated in psychiatric institutions and to demonstrate that a psychiatric diagnosis is stigmatization and prejudice, not medical science.

In 2005, Dr. Antonucci received CCHR’s “Thomas Szasz Humanitarian Award,” an award introduced in honor of CCHR’s co-founder Prof. Thomas Szasz, with whom Dr. Antonucci shared the same libertarian views and opposition to coercive psychiatry. In response to the award, Prof. Szasz said, “I am delighted to welcome and salute my old and good friend, Dr. Giorgio Antonucci. His long-standing, courageous, and effective efforts to liberate psychiatric slaves in Italy from their bondage makes him an eminently worthy recipient of CCHR’s Thomas Szasz Award.”

In 1968, Antonucci and several other doctors formed a group that organized an alternative hospital ward to the traditional psychiatric asylum. The policy was: “Never use restraints.” They hired nurses not trained in psychiatry and, therefore, not biased toward psychiatric ideas. The success rate was unprecedented. He first worked in Cividale del Friuli, a public hospital ward and first Italian alternative to mental hospitals. The following year—in 1969, the year CCHR was established—Antonucci worked at the psychiatric hospital of Gorizia, directed by psychiatrist Franco Basaglia who, like Szasz and Antonucci, proposed the dismantling of psychiatric hospitals that relied upon involuntary detainment and enforced treatment.[1]

Antonucci criticized the fact that in this hospital electroshock use was stopped in the treatment of men and exclusively used on women.[2] He believed that there were numerous compassionate and workable, non-psychiatric programs for disturbed individuals without resorting to mind-altering drugs and brain-damaging electroshock. Such individuals are not “ill,” but are either in suppressed physical pain or have problems in life that can be resolved.

Even during his medical training, he had held such beliefs. He was expected to mask the delusions and fears of patients with mind-altering drugs, but he refused. He rejected the idea that such delusions were a symptom of “schizophrenia” because this idea never led to a cure—only to more drugs.

Through humane care Dr. Antonucci brought patients out of their state of mental and physical torture.

In 1973, his work led him to other Italian asylums, infamous for their concentration camp like conditions and in particular, the institution of Osservanza (Observance) in Imola, Florence. Fifteen psychiatrists challenged Antonucci, giving him a ward of 44 women they said were “incurable” and violent—so violent they had been restrained for years. The women had been subjected to electroshock and given heavy psychotropic drugs. Entering the ward, Dr. Antonucci confronted unspeakable horror and unrelenting screams from the straight-jacketed patients. But one by one he removed their restraints. One by one, they came alive.

In his book, The Lessons of My Life: Medicine, Psychiatry and Institutions, Antonucci explained his opposition to the use of restraints: “If a cat is kept tied up, after a while the cat will be found dead. Man resists a bit more, but it is clear that immobility is against our physiology. We are born to move; without movement, muscles begin to atrophy. When I untied these people, they couldn’t stand up, they would fall to the floor; I had to begin by accompanying them or have them accompanied, to let them get their muscular function back.”

“After many years in bed, their hands and feet strapped down, straight-jacketed and, sometimes, wearing a sort of a muzzle to prevent spitting, dirty with their own excrement, they didn’t want to dress or walk. They could not even eat. Many of them had broken teeth due to electroshock…. It was like resuscitating them from death,” he added.

Antonucci was met with enormous opposition from psychiatrists, their nurses and staff, describing how he was twice beaten, “not by the patients but by the nurses that were opposed to my methods, because they thought that they would lose power because I had altered all the hierarchies with my attitude.” Still, he persisted and his patients went to the European Parliament to speak for themselves and to defend their rights.” They started again to walk, to speak. They started again to communicate with others,” he said.

Through humane care he brought them out of their state of mental and physical torture: “I began talking to each of the patients,” he said. “But I never forced them to talk.” He changed the metal doors for glass ones. He bought a fountain and installed it at the front door. He got local artists to come to the asylum to paint beautiful murals on the walls—in short, he turned a prison into a humane sanctuary. Florence musicians taught the patients music and nurses taught the patients to wash and dress for the first time in decades. Proper medical examination determined the patients suffered a myriad of physical conditions, including heart disease and tuberculosis. These were successfully treated.

Through humane care he brought them out of their state of mental and physical torture: “I began talking to each of the patients,” he said. “But I never forced them to talk.” He changed the metal doors for glass ones. He bought a fountain and installed it at the front door. He got local artists to come to the asylum to paint beautiful murals on the walls—in short, he turned a prison into a humane sanctuary. Florence musicians taught the patients music and nurses taught the patients to wash and dress for the first time in decades. Proper medical examination determined the patients suffered a myriad of physical conditions, including heart disease and tuberculosis. These were successfully treated.

“It took me five years of very hard work to restore confidence to these women; five years of conversations, even at night, of relationship face to face. This is not a technique, but a different way of conceiving human relationships,” he said.[3]

Unrelentingly, this great doctor showed nurses that miracles could happen. After a few months, his “dangerous” patients were freed from their psychiatric prison. In 1997, Imola was shut down. Against tremendous opposition from his peers, Dr. Antonucci dismantled some of the most oppressive psychiatric wards by treating his patients with respect and dignity.

Working with the CCHR Italy chapter, each year he presented the “Antonucci Award” to those who distinguished themselves in the defense of patients’ rights. These awards shall continue as a legacy of his work. As CCHR Italy wrote, “Giorgio passed away, but his example and his ideas will live on, illuminating the path for those who want to engage in defending human rights in the field of mental health.”

Quotes from Dr. Antonucci:

- “I think that often, in addition to the hazard of psychiatric opinion, the most dangerous thing is when a person resigns to his own conviction of being sick.”[4]

- “Inside the mental hospitals, it wasn’t mad people who were locked up—as it’s usually believed—but unlucky people who happened to find themselves in hard situations.”[5]

- “I opened the doors and I took away the drugs, because [the patients] were crammed and bloated with drugs, but the essential belief was that these were people like us, who have to live freely, not like deformed objects to keep in cells like monsters.”

- “For me it means that [mental illness] does not exist and psychiatry must be completely eliminated. Doctors should only treat body diseases.”[6]

- “Forced treatments are violations of their rights and harmful to them, to their thoughts and their lives, therefore I started dealing with psychiatry.”[7]

- “For me, to free the people from the treatments of psychiatry, or, to free people from internment in an insane asylum, has mostly meant to see people that seemed finished, both mentally and physically, return to life fully and to regain all those abilities that they had before they met psychiatrists.”

- “The mind continues to discover things about itself, but it is infinite like the sea. This is one aspect, and this aspect must put us in the position of having great respect for others, not having little respect as psychiatrists often do when they take a person they have incarcerated, and have reduced that person to pieces.”

- “I found a man that sat in a chair in silence for years. For years he was immobile and he didn’t talk to anyone. I sat next to him. The first time, I would also sit in silence. We looked at each other. Then, with some of my initiatives, he also tried to copy them. If, for example, I would get up to go to the other side of the room, he would also come, because a connection was established without words…I stayed together with that man, first in silence, then doing things together, also in silence, then starting to talk. One day, while the others were playing, I took the ball and threw it to him; he grabbed it, with a movement he hadn’t done for years. I went around with him, taking trips, we moved and talked. This man had closed himself in silence, because he didn’t have any real motive to talk to anyone for years.” – Giorgio Antonucci, The Lessons of My Life: Medicine, Psychiatry and Institutions.

- The international [United Nations Universal] Declaration of Human Rights declares that each one of us has certain rights: civil rights (one can get married or not marry); political rights (one can vote or not vote); economic rights (one has the right to dispose of one’s own money), and cultural rights. The only thing I did was to give back to these people the rights foreseen by the United Nations for each citizen of the world.”

- “I have never had any doubt about the fact that psychiatry is a system of aggression.”

- “Whoever thinks that the methods of psychiatry are useful or even essential has understood absolutely nothing.”

- “I think that psychiatry must disappear because it is a system of control of ideas and it doesn’t have respect for freedom of thought.”

Refences:

[1] https://absoluteprohibition.org/2016/03/25/the-mad-hatter-presents-a-conversation-with-dr-giorgio-antonucci/.

[2] https://absoluteprohibition.org/2016/03/25/the-mad-hatter-presents-a-conversation-with-dr-giorgio-antonucci/.

[3] https://absoluteprohibition.org/2016/03/25/the-mad-hatter-presents-a-conversation-with-dr-giorgio-antonucci/.

[4] https://absoluteprohibition.org/2016/03/25/the-mad-hatter-presents-a-conversation-with-dr-giorgio-antonucci/.

[5] https://absoluteprohibition.org/2016/03/25/the-mad-hatter-presents-a-conversation-with-dr-giorgio-antonucci/.

[6] https://absoluteprohibition.org/2016/03/25/the-mad-hatter-presents-a-conversation-with-dr-giorgio-antonucci/.

[7] https://absoluteprohibition.org/2016/03/25/the-mad-hatter-presents-a-conversation-with-dr-giorgio-antonucci/.

SHARE YOUR STORY/COMMENT