Note from CCHR: The fact that there is a proposed ban on electroshocking children is good news. The fact that children are being electroshocked is abhorrent. The truth is, that more than 1 million people are electroshocked every year, including the elderly, pregnant women and children. Even toddlers. The practice needs to be banned across the boards. Period. Read this for the actual facts about ECT by psychologist John Breeding, “Think They Don’t Electroshock People Anymore? Think Again, Even Toddlers and Pregnant Women are Being Shocked” http://qr.net/eplm

The Age, Australia – July 30, 2011

by Jill Stark

ELECTRIC shock therapy on young children will be banned and psychiatrists could be jailed for carrying out the controversial treatment on teenagers and adults without strict legal checks, under proposed legislation.

Under a review of Victoria’s Mental Health Act, new legislation has been drafted that would outlaw electroconvulsive therapy, also known as ECT, for children aged 12 and under.

Doctors would still be able to use it on 13 to 17-year-olds without their parents’ consent if they can convince a mental health tribunal that all other treatment options have been exhausted.

The same rules will apply to adults, with the final decision on whether to use shock therapy taken out of psychiatrists’ hands and given to the tribunal. Doctors who breach the laws will face up to a year in jail.

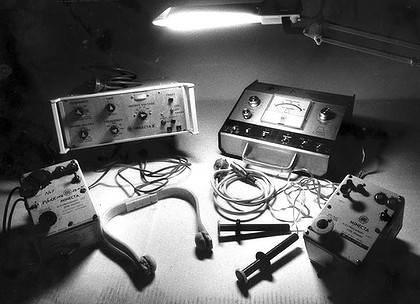

The treatment, immortalised in the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, induces seizures by delivering an electrical current to the brain.

Proponents say the movie unfairly stigmatised the procedure, and the use of anaesthetic and advances in technology have made it safer. But its use on children, whose brains are still developing, remains contentious.

ECT is usually used to treat patients with severe depression or extreme mania whose conditions have not improved with other treatments. While it is still unclear how the treatment works, it is thought the shock-induced seizures affect chemicals in the brain that influence mood.

In submissions to the mental health review, legal groups including Youthlaw and the Law Institute of Victoria, along with Child Safety Commissioner Bernie Geary, the Mental Health Council of Australia and the national depression group beyondblue, have welcomed the changes, saying they provide greater protection for vulnerable patients. Others want the legislation to go further, with a complete ban for anyone under 18.

However, psychiatrists say the new laws are too punitive and could lead to increased suicides as severely depressed people are denied ”life-saving” treatment.

Last year The Sunday Age revealed there had been a 10 per cent rise in the number of patients receiving shock therapy since the previous year.

Almost 20,000 sessions were carried out on 1791 patients in Victorian hospitals in the 2009-10 financial year, including 46 sessions on seven children under 17 and a further 163 on an undisclosed number of 18 to 19-year-olds.

In submissions, the Australian Medical Association, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists and the Victorian branch of the Australian Nursing Federation called for the draft bill to be amended to allow shock therapy on children.

Doctors from the University of Melbourne department of psychiatry mounted the most strident objections to the changes, arguing they imply doctors are ”evil and want to harm their patients”.

One of the doctors, David Castle, who is also chair of psychiatry at St Vincent’s Hospital, told The Sunday Age that while shock therapy on children was extremely rare, it was a valuable treatment option.

”Anything that categorically bans it could be enormously damaging because some youngsters do get very severe depression and ECT is an extremely effective and very safe treatment. The new law means it’s going to be very difficult to give it to a patient, especially in an emergency when people are in a totally dire situation where they’re not eating or drinking or intensely suicidal,” he said.

Under the draft laws, doctors would be limited to a maximum of 12 sessions of electric shock therapy per patient and would have to seek permission from a mental health tribunal.

Youthlaw’s submission expressed concern about the effects of shock therapy on the developing brain and called for a ban on the treatment for patients up to the age of 25.

A spokeswoman for Mental Health Minister Mary Wooldridge said the reforms were complex and the state government was reviewing feedback.

SHARE YOUR STORY/COMMENT